It's Not Always About Doing What You Love: Lessons from My Old World Mom

How a mother's memories help a first-generation American set attainable goals and cope with social media addiction.

By Sarah Hachem

A typical day for me looks like this: I pace back and forth from the tiny kitchen to the big dining room, while heavy plates test my hands and my fingertips clutch their edges. Securing everything together for another few seconds, I anticipate the moment I finally get to release the dishes onto the table. I smile politely and prepare to repeat this transaction over and over again.

And over and over again, I watch as dozens of dishes that tempt my appetite satisfy others.

When my waitressing shift ends, I begin what I like to call my “Second Shift,” or, the time I have left after work. Recently, I’ve spent this time building good habits for myself that I needed, yet for too long, refused to admit.

My Second Shift used to look like this: scrolling through Instagram and TikTok, feeding my appetite for more and more. I wanted a prettier, expensive closet, with fabulously long dresses; I wanted to fly to Casablanca on a whim; I wanted to live lavishly in a house with room for a desk, so I didn’t have to go to the library to study. I wanted my life to miraculously change into the glamorous lives of those I followed online. I wanted a slice of the sweeter pie everyone but I seemed to indulge in.

Sarah Hachem relieving a stressful day by playing with her pet cat in Dearborn, Michigan.

With envy and disappointment, I’d head to bed at 3 a.m. Even the daily notifications alarming me that screen time increased didn't stop me from repeating this same routine.

I discovered that my friends shared the same screen-time obsession. “Instagram posts always show me things I should ‘fix’ about myself through trending makeup tutorials or workouts,” says Fatima Alhussani, a friend from Dearborn, Michigan.

Another friend, Mauria Muthana, described her struggle. “I know that social media keeps me distracted from thinking of healthy ways to destress,” she says, “but I just keep scrolling.”

I knew I wasn’t alone, but that didn’t solve anything. I needed help, but for me and many other teenagers, asking for help evokes an abundance of anxiety. And because I come from a culture where mental health conversations aren’t normalized, directly asking for help from my mother seemed impossible.

Her youth in the farming village of Aienitni (pronounced i-nee-ti-nee), Lebanon, contrasted with mine as a waitress in Detroit. I already knew this built borders between us. Now, though, I wanted to break what separated us and put effort into understanding and integrating my family’s sometimes-confusing Lebanese customs, with my long-established American ones. Instead of directly asking my mother for help, I asked for stories.

She always described her youth as “happy and productive”, so recently, I asked her to tell me more. I wanted to identify the differences between her life at 18 and mine. Although stories weren’t exactly what I wanted, they opened my eyes to all I didn’t see before.

Every day, she, my aunt and their mule awakened at 5 a.m., before the sun rose. Their mission was a 2-mile walk to the local well, to round up 8 gallons of water. My mother and aunt carried 1-pound bottles on their heads and two 5-pound bottles on each arm. They left early in the day to avoid hot weather, and long, pushy crowds, my mother said, in Arabic.

This was just one of the many struggles she faced living in poverty.

Fatima and Ibrahim Hachem, my parents, posing in front of the farm they worked on. Photo courtesy of Abdulmajeed Hachem

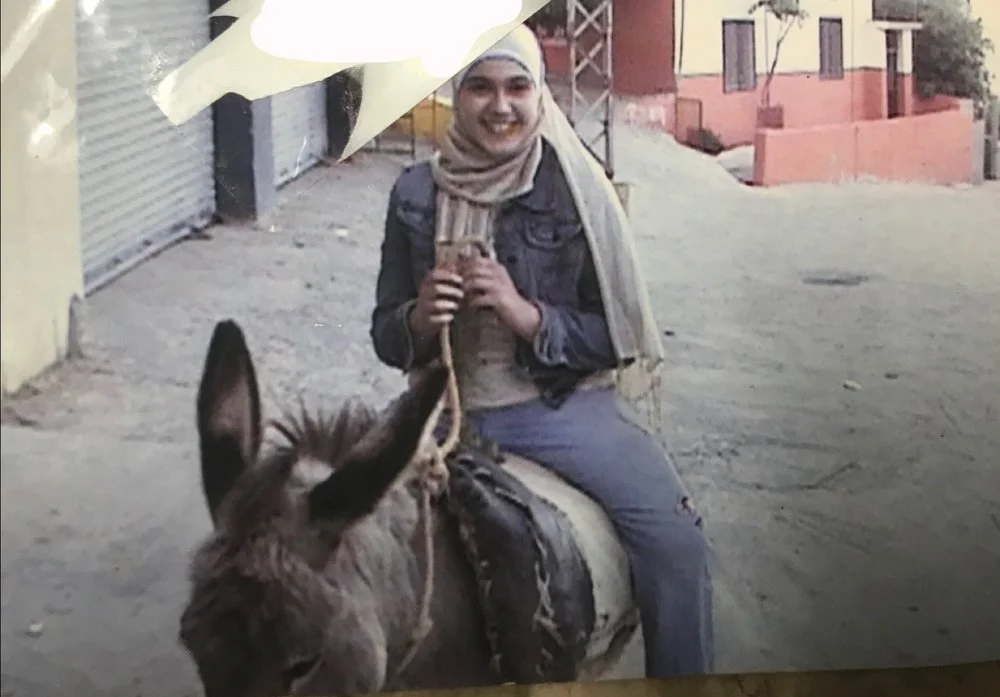

My mom’s pet mule, ridden in Lebanon by my sister Mariam Hachem. Photo by Ibrahim Hachem

She told me she spent the rest of the day cooking, cleaning and feeding the barn animals, and these tasks weren't simple either: To cook, she needed to pull out ingredients from the farm, which mostly grew figs, turnips and bulgur. Every other ingredient needed to be paid for with small sums of money they mustered by selling their own produce.

“Didn’t you feel trapped by that hard work, that struggle just to survive?” I asked her. “Yes, the work frustrated me sometimes, but I realized that my family needed my help, and so I needed to help. My mom, my dad, even my friends, they all lived the same life as me, did the same work,” my mother said.

I noticed her routine included a lot of things that mine didn’t. Apart from a relentless amount of work, she was surrounded by people who lived the same lifestyle and had the same feelings when they completed the same work. I realized this might be why mental health-related topics became taboo in our Lebanese culture: Talking about struggling more or differently than others can seem selfish in communities where everyone faced identical battles. This made me realize that parts of my culture I didn’t “like,” were actually just parts I never properly understood.

My mother told me that after her first shift was over, she knew exactly how to spend the second. If she felt lonely, she invited her friends to drink tea and walk around the village. If she felt creative, she would draw the birds that flew in the sky above her. If she felt insecure, she would brush her hair and paint her nails. If she was energetic, she would visit her aunt, who owned the first TV in the village. There, she could follow an exercise routine on the fitness channel.

My mom, Fatima Hachem at 20 years old, relaxing near a lake in Lebanon. Photo courtesy of my dad, Ibrahim Hachem

I realized then, that just like my mom, I should learn to identify what I needed throughout my day. My habit of reaching for my phone when I couldn’t handle my own emotions was leaving me feeling purposeless. It was time to change.

Now, I start my Second Shift by identifying how I’m feeling, changing or empowering that feeling, and practicing gratitude for myself, and Allah.

It's simpler than I imagined: When I feel depressed about my first nine-hour shift of the day, I challenge myself. Instead of thinking, “I have to do this,” I try to appreciate my role in bridging the gap between the hungry diners, and a kitchen staff eager to cook, and think, “I get to do this.” When my space feels messy, I clean. When I feel slothful from the cheeseburger I gobbled for lunch, I make a salad for dinner. When I feel thankful, I pray. When I feel proud of myself for handling the day well, I write down a plan so the next day goes even better.

What I learned from my mom is that chasing our cravings might not satisfy us the way we hope — that doing what excites you at the moment isn’t as important as doing what matters. Yes, I enjoy watching TikToks more than serving tables or making my bed, but serving tables pays, and making my bed makes me feel productive, so I’ve prioritized that. For my mom, taking 2-mile walks to fetch water wasn’t what she enjoyed, but it kept her family healthy, so she prioritized that.

Intertwining my two cultures with the help of my Mama has brought me closer to understanding that chasing what makes us physically, mentally and spiritually healthy helps us balance the best and worst parts of life.