A Wish to Remember: Camps for People with Muscular Dystrophy Lead them Toward the Stars

Hope overpowers the darkness for people with muscular dystrophy who attend a life-changing camp.

By Torrance Johnson

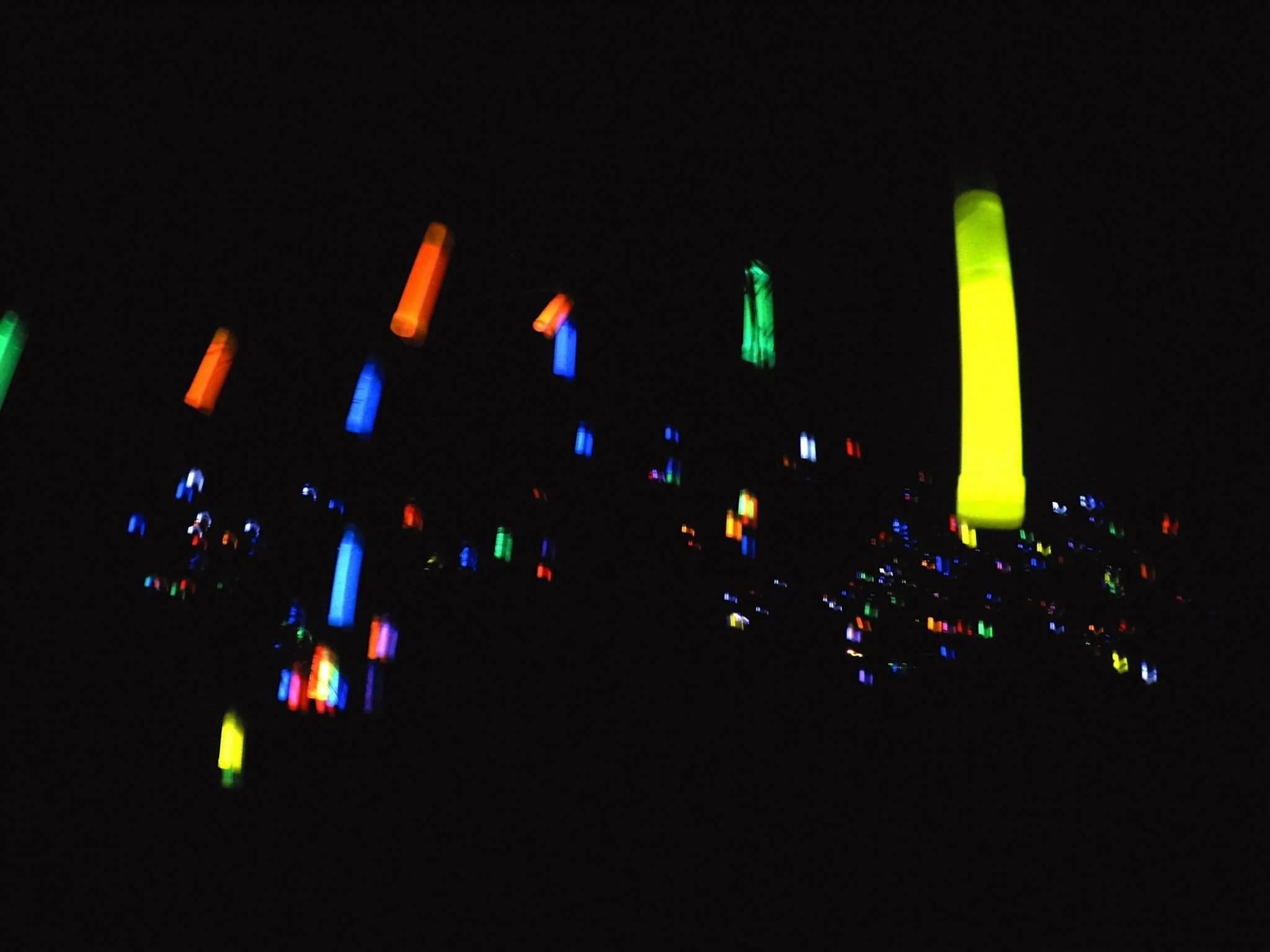

As I sit in front of a 50-foot tree 3 feet wide tree covered in rows of glow sticks — with one slot still empty — I think of the friends and loved ones I’ve lost throughout my life. The cherished memories flood my mind like raindrops as they become a puddle. From my hand dangles the missing glowstick uncracked, as the time isn’t yet right.

While my soul rejoices that my lost friends are running around happy and alive in the afterlife, my heart aches at the fact that they are no longer by my side. Though this ache is soothed by some of the friends who are still here as we sit, parked side by side. Having them there to comfort me gives me the strength I need as I crack my glow stick, say my wish and set it on the Wishing Tree.

Glow sticks hanging from the Wishing Tree represent the wishes made. Photo by MDA Greater Detroit Camp photographers

Let’s Go Camping

Tucked away in the woods by Lake Huron is a campsite that hosts camps for kids and adults with muscular dystrophy. Muscular dystrophy is a disease that causes weakness and decay of muscles and affects the nervous system, according to the Muscular Dystrophy Association. Many neuromuscular conditions can fall under muscular dystrophy, though they might have fundamental genetic differences. The main factor these conditions share is that they are genetic conditions that affect the body’s muscular system causing weakness, decay and impaired sensations.

Despite the limitations these conditions could cause, summer camps allow people with these conditions to be more than just their limitations. The Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA) Summer Camp is for ages 8 to 17, and the Volunteers Assisting the Disabled (VAD) serves those over 18. These camps exist solely to put a smile on campers’ faces and to connect them with other people with similar conditions.

Before camp, I was extremely extroverted, charismatic and just as funny, so making friends wasn’t too hard. Though I had friends, I often found myself as the only wheelchair user or the odd man out in many of the places I went. People would stare. They’d point. And they would whisper as if I was unable to hear their words or feel their eyes on my skin as they stared.

This all changed when I went to MDA Summer Camp in Lexington, Michigan at 6 years old. For the first time, I was surrounded by 100 people just like me. The feeling was indescribable. Everywhere I looked there was a camper whom I found some similarities with — from wheelchairs to crutches, to those who could only take a few steps before exhaustion caused them to seek a wheelchair.

During camp, I was placed in a cabin with five other campers, and two of the campers shared an age as well as the condition I have called spinal muscular atrophy. The three of us grew close due to our similarities. Each year we remained cabinmates, and our familial bond strengthened.

We talked about things other people just wouldn’t or possibly couldn’t understand. It was as if we all looked at the world through a similar lens; we could all look at the sky and see the same blue. In and outside of camp the relationships built there helped mold us as we went from children to present-day adults.

At camp, we are able to do activities that most people without conditions can do. The week is filled with smiles and laughter as wheelchair-bound campers are able to go horseback riding and swim in Lake Huron. But beyond activities, the camp community is one big family, which is what makes these camps so special.

Every part of camp was of interest to me, and I participated in it headfirst, though sometimes I needed just a little help. I’m from Detroit so seeing the horses was startling. I was nervous at the sight of the seemingly huge horses while also captivated by them. Through some mild convincing, I was placed on a horse with someone behind me to manage my balance. My counselor walked alongside the horse mainly to keep me calm. I rocked back and forth on the horse as it slowly walked step by step.

Torrance Johnson riding a horse at MDA Camp in 2014. Photo via MDA Greater Detroit Facebook

The camp organizers help create long-lasting memories that give everyone a smile, even on their dark days. Extremely passionate and cheerful volunteers plan activities and my personal favorite: skits. Each year, they’d put on shows for young campers designed to put one more smile on our already beaming faces. My personal favorite was the magic show featuring Magico and Razzmatazz. This joke-filled magic show got all campers engaged and laughing as the volunteers tried to pull off tricks for the crowd. As I write this, the glow on my face lights up my now bright room.

Though the camp is full of joyous times, it still acknowledges the unfortunate sadness that is the loss of loved ones. On the last day of camp, a ceremony at dusk is dedicated to the individuals who have died, and we light a glow stick in their honor on the Wishing Tree. During this time the community comes together holding each other near as tears are shed and memories relived.

The first time I experienced the Wishing Tree I didn’t fully understand it. I knew it was something we were doing to honor our loved ones, and while many people were crying, I didn’t fully understand why.

People came up to me with tears streaming down their faces as if the waterfall of their hearts just poured out its sadness. Squeezing me tightly, they latched on to me, clinging as much as they could. Person after person would latch, creating a somber atmosphere, especially for those who resonated with the ceremony.

I didn’t get it. I would hug everyone back and remain silent, giving them time to mourn, but the true meaning was lost on me. I hugged those that came to me as a reflex, not as an intention. While others saw the pitch-black sky, I saw the still-shining sun as it worked its way down the horizon. I saw the darkness taking over the sky, but it wasn’t my focus, at least not yet.

Camp Is Like Home

Every camper is free to just enjoy themselves and be happy with a community of people like them. While not all campers are wheelchair-bound due to varying conditions, the shared experiences are just one of many layers that make this camp a family. At the camp, we have a song written for our Michigan branch that perfectly sums up the meaning of camp. Written by long-time camp volunteer Karen MacDonald, the song’s chorus says, “Where some of us roll and some of us walk, yea we’re all the same in this magical place.” The song “Camp is Like Home” was inspired by the campers, as many say, “it’s like home, it’s a family.”

Ian Zurawski, 17, is a wheelchair-bound camper and close friend of mine with spinal muscular atrophy. “You really just make and find your people, and you make a family — one that you’ll never forget,” Zurawski says about the camp community.

The reality of having a neuromuscular condition is not lost on me for reasons beyond personally having one. I’ve also lost many friends to these conditions, as several types of muscular dystrophy will eventually lead to the death of those with it.

Zachary “Diezel Train” Davis was a bright-eyed and profane camper with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. With a soft raspy voice and a mouth that had no filter, he said how he truly felt, and enlightened others while doing so.

Once, while riding together at camp, I kept saying “excuse me” to people in our way. Diezel said, “Just keep going. They’ll move.” Then he said, “If they don’t move. Just run them over.” This summed up Zachary. He was one of a kind, the likes of which we aren’t to soon see again.

Zachary was more than a friend to me. A brother is the only way to put it. Though he is no longer here physically, his words of wisdom still stay with me to this day, nearly three years after his passing.

While I am unable to quote him directly due to his profane tongue, something he said that stuck with me was “not to be scared.” Through any challenge I take on, I remember his words, and no matter how scared I might be, I roll forward with my head held high. Zachary loved wrestling, loved the ladies and, most importantly, loved his family, which I am proud to say I was a part of.

Torrance Johnson (left) and Zachary Davis (right) at camp in 2014. Photo via MDA Greater Detroit Facebook

Dominic Davis, Zachary’s brother, experienced the atmosphere as well as the community of the camp.

Dominic expressed the impact and just how much it meant to Zachary: “Camp Cavell will forever hold my brother’s heart and soul here on earth.”

A Wish to Remember

Zurawski describes the Wishing Tree as “the heart of camp.” It serves as a way to honor loved ones and connects those still living to those who are not.

The Wishing Tree ceremony takes place on the last day of camp at dusk. As the sun starts to set and the gray light takes over the sky, everyone at camp grabs a glow stick and surrounds the Wishing Tree. The faint sound of children laughing in the distance contrasts with the soft sobs.

This is a time for quiet.

This is a time for reflection.

A time to pay our respects and remember the deceased.

And a time to make a wish for our future.

Camper Justin Wilton sits under the Wishing Tree looking to the skies. Photo via MDA Greater Detroit Facebook

While we honor the deceased and look forward to the future, we hold each other tight so that if only for the last time, we’ve shared one more embrace. As I grew and matured seeing loved ones die, watching them win battles and losing others, I slowly started to see the same pitch-black sky that others saw.

This year as I made my way to the tree I parked a distance away from it. Past memories crept into my mind like a shadow through a slightly cracked door, and the blue sky started to appear. The smiling faces of fallen friends in my mind began to fade as new friends and others who had matured and lived, remaining active in their fight, came into focus. Like a dam, I tried my best to contain my tears. I succeeded until words of encouragement were spoken.

The first crack in the dam was caused by Patrick, a friend who knew a younger me and spoke of how proud and amazed he was at my personal growth. The second came as another friend a few years younger named Colin served as a sage, saying, “Torrance, being there for others is good, but don’t forget to share your burdens with others.” I replied, “Those are some wise words,” to which he said, “I learned from you.”

My cracking dam started leaking and tears started to come out of my eyes. My dam shattered into a million pieces when someone came up to me with open arms. For a while, we sat there, locked in a hug crying on each other’s shoulders. At this moment no words were shared because they weren’t needed.

An eternity passed by during this hug, and the kid who never stopped talking became a man who chose his words carefully and knew when they weren’t needed. At the end of our hug, she tells me how one of her friends waits until everyone leaves the Wishing Tree to hang their light. With no intention, I found myself with my friends at the tree after everyone else had left with my uncracked glow stick.

The last part of the Wishing Tree focuses on one of the most powerful things in the world: hope. Another key part of the Wishing Tree is to make a wish that is up to each person’s discretion. Hope for the future, a message to a loved one.

Dominic Davis says it best when talking about his goal: “To raise awareness (about) this disease and what it CAN’T TAKE from our community — HOPE.”